The Doctor in Print

Posted by Frans Laurentius on 10.11.21

Recent acquisitions from a medical collection.

Recently we aquired a large collection of portraits of doctors, physicians and prints with medical subject matter. This collection was assembled in the period between the two World Wars. The dates range from the 16th. century up to the early 19th. century and the prints include many rarities. Here, we will show you some of the more interesting items in greater detail.

Firstly, a drawing in black and white chalk on blue paper. The drawing is a sketch of a woman leaning on an object. The watermark, a foolscap, makes it possible to date this work to around 1667-1669 1.

The object is what makes this drawing medical. It is a tube with a lid, made of wicker. These containers are encountered frequently on Dutch 17th. genre paintings. Very delicate glass urinals were transported in the wicker containers. This was used for the examination of urine, or as it was called, " Piskijken" 2. By examining the color of the urine when holding the glass to the light, the doctor was able to make a diagnosis. Even in the 17th. century this method was considered to be spurious; it was depicted in many paintings with a comical or moralistic content. It is very well possible, that this sketch was made in preparation of a painting. Although the drawing is not signed (as often with these drawings) it is possible to give it a place in art history. Many of the mentioned paintings were made in Leiden by a group of painters known as the “Leidse fijnschilders”. They specialised in very finely painted works with genre subject matter. Artists include Gerard Dou, the Van Mieris family, Jacob Toorenvliet and many others. Piskijken was amongst their favorite subjects; however we could not ascribe this work to a specific artist from this school. The painter Pieter Cornelis van Slingeland would be a possible maker.

There are three portraits of Frere Jacques de Beaulieu (1651-1714) present in the collection. This former mercenary soldier would go on to work as a autodidact lithotomist, specializing in the removal of kidney stones. In 1690 he renounced his worldly life, dressed as a priest and conducted all further operations pro deo. Already during his life opinions about his medical abilities were divided; he had to leave France after a disastrous operation. Travelling through Europe he visited the Netherlands in 1699, where he was quite the sensation 3. This resulted in a demand for his portrait, and many prints with his depiction were made in a very short period. Here are two examples, a large one made by Pieter van den Berge (above) in etching and a smaller mezzotint made by Jacob Gole (below). Beaulieu, mezzotint by Jacob Gole.

Of utmost rarity is an impression of the portrait of one of the most famous physicians in the Netherlands, Hermanus Boerhaave (1668-1738). This multi-talented man was highly influential with his new methods and known throughout Europe. He is represented with several portraits in this collection. The famous artist Cornelis Troost (1696-1750) painted his portrait in 1738 and also made a small etching and a mezzotint. He probably made this for the family of Boerhaave, which made the printed edition very small and rare.

The famous botanist Carolus Clusius is represented by a beautiful Mannerist portrait by Jacques de Gheyn II, published in 1601. Surrounded by flowers, seeds and other botanical items, the founder of the Hortus Botanicus in Leiden looks at us.

Next is a person who was portrayed by both Rembrandt and Jan Lievens during his life. In this case we have the portrait etched by Jan Lievens (1607-1674). It concerns the famous Sephardic physician and publisher Ephraim Buono (1599-1665), a close friend of Menasseh Ben Israel (who was incidentally also portrayed by Rembrandt).

A typical mezzotint by Pieter Schenk depicts the famous anatomist and collector of medical oddities, Frederick Ruysch (1638-1731). Ruysch devised a new method of preservation of specimens: arterial embalming using a secret recipe. Using this method he created a Cabinet, a museum in five rooms where these specimens were exhibited. ‘Ruysch's cabinet' or museum was described as “a perfect necropolis, all the inhabitants of which were asleep and ready to speak as soon as they were reawakened”, and attracted many visitors. A large part of his collection was purchased by Peter the Great.

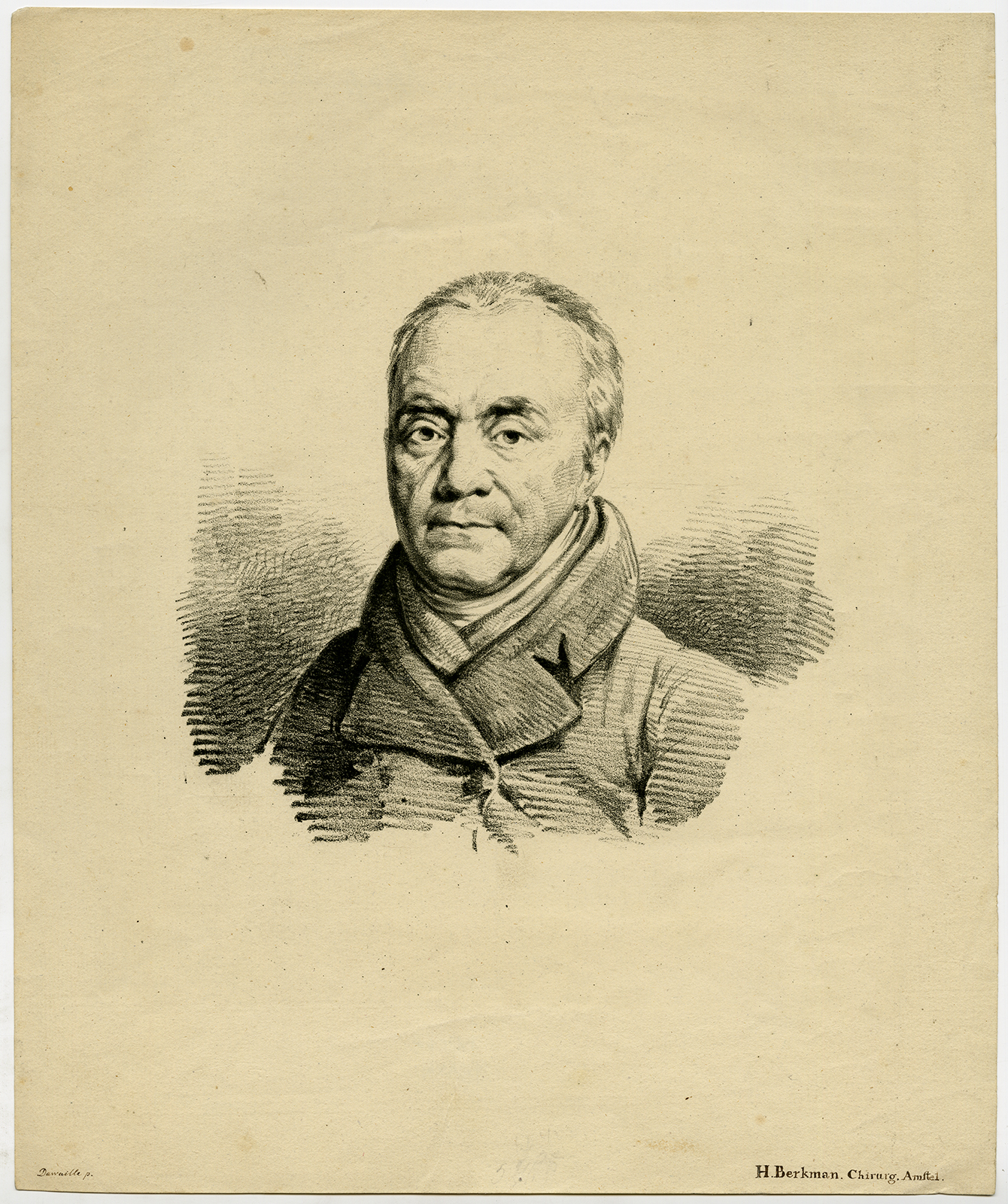

This portrait of the physician and obstetrician H. Berkman from Amsterdam is a very rare and good example of early Dutch lithography from around 1820. It was made by Jean August Dawaille (1786-1850), father-in-law of the famous Romantic painter B.C. Koekkoek.

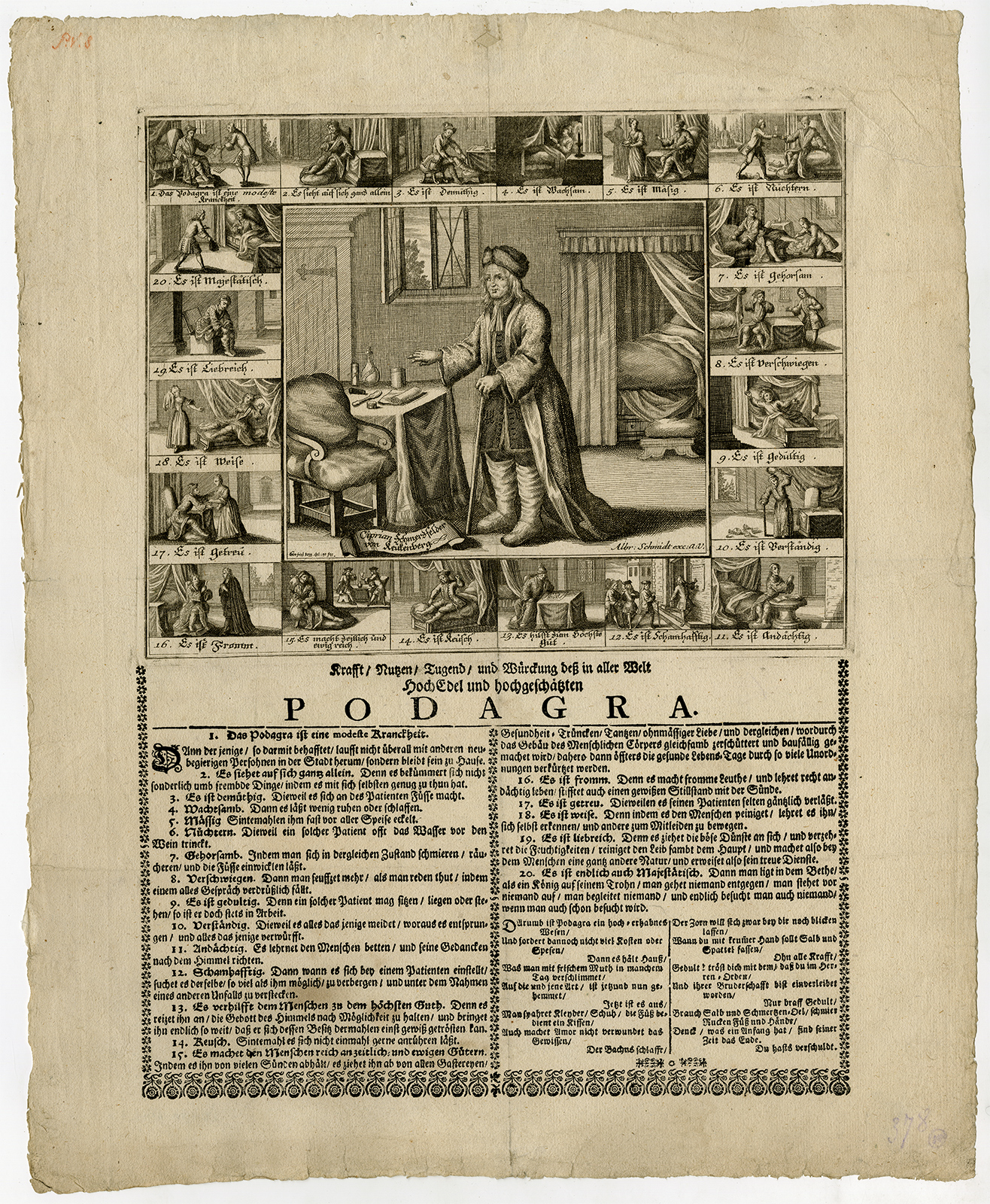

We end this overview with a very curious pamphlet published in Augsburg around 1720. It lists the 20 advantages (!) of Podagra, or gout. These include: ‘Gout is loyal, while it never really leaves a patient’ and ‘Gout is vigilant, because it allows little rest or sleep’. A comical but very strange way of explaining an illness, indeed! You can find all these recent acquisitions, and more, on our website.

Notes:

- Laurentius, vol. II, nrs. 373, 374 and 375, dated 1667, 1669 and 1668. It is paper from the Veluwe area.

- See catalogue to the exhibition “Van piskijkers en heelmeesters”, Museum Boerhaave, Leiden, 1993-1994, p. 26.

- Idem, p. 27.